‘Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time’ details grinding reality for Manus Island detainees

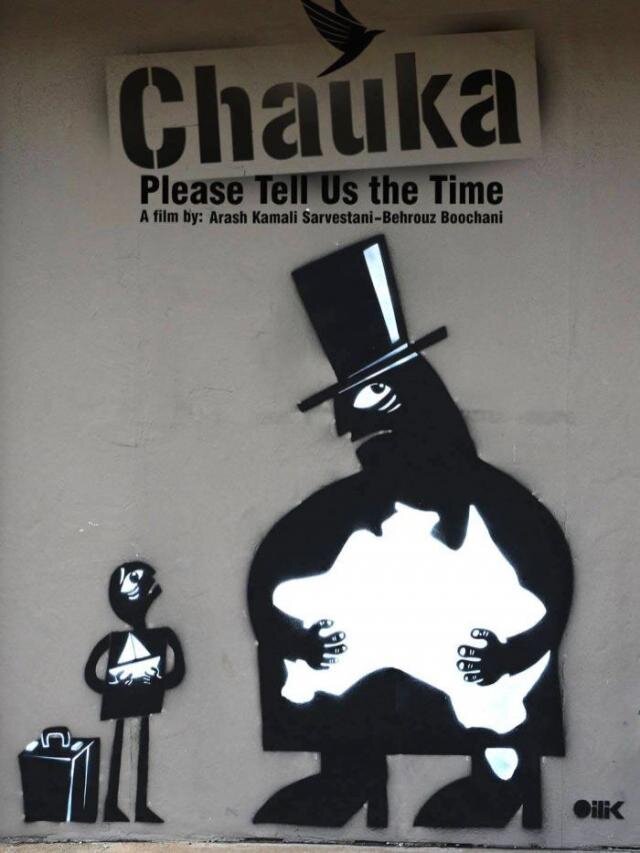

Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time

Written & directed by Arash Kamali Sarvestani & Behrouz Boochani

Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time is a ground-breaking film that gives audiences a new window to look into Manus Island detention centre.

In many ways, the method of the film’s creation and the connection it began having with society before one frame had been screened, is its greatest achievement. The Sydney Refugee Action Coalition held a rally and march to the film’s premiere, which included a message from the film’s co-creator Behrouz Boochani.

At the Sydney International Film Festival premiere, there was an empty seat next to co-director Arash Kamali Sarvestani. The seat was for Boochani, the Iranian journalist who has spent the past four years in Manus Island detention centre. His writings on social media and the media have laid bare the human rights abuses in the detention system.

Boochani was officially invited to the festival, but the Australian government denied his visa application. He spoke to the Q&A from Manus Island, saying he hoped his letter asking for a visa and the official denial would one day end up in a museum.

Chauka, through the use of footage secretly recorded on phones, explores daily life inside Manus Island detention centre, the native Chauka bird and its connection to Manus Island’s culture.

The film originated when director Sarvestani read Boochani’s writings in The Guardian and contacted him to ask if he wanted to make a film. Boochani spoke to several directors previously, but none shared his vision for the film in the way Sarvestani did. They both wanted to make a poetic film, rather than a more journalistic or character-driven narrative.

Theirs was a relationship developed over more than 10,000 minutes of phone calls during the film’s production.

Its style was inspired by internationally respected and socially conscious Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami, who believed film was powerful when it gave the audience the opportunity to look at a context from the outside without the filmmaker trying to force their views on the viewer. Rather, the audience is encouraged to think for themselves about what they are watching.

Sarvestani explained that they were “creating a frame for the viewer to look through” into Manus Island detention centre.

It is a style that Sarvestani admitted may cause some to get bored through the film. He urged audiences to sit until the end, saying it was when you dwelt on the film long after its screening that it came together.

It is a style that results in a very loose film, from framing, editing and music to narrative and characterisation. This can make the film difficult to follow.

You get a frame into the day-to-day life inside the Manus Island camp from difficult phone calls to relatives back home, and the endless sitting, pacing and sitting. There are endless hours staring at the sea through fences while detention centre staff go about their duties in a drone-like manner.

The footage is often dull, numbing, devoid of life. It is in contrast to footage that focuses on intense moments, such as guards assaulting people, rather than daily, often torturously dull life inside detention.

The narrative shows these vignettes of life in the centre, such as the food being delivered pre-made in plastic containers, though it rarely seems to be going anywhere. While you get to see these moments of people’s lives, you never hear their stories or why they are seeking asylum.

This narrative style is effective at capturing life in detention and the effect it is having. But it makes it a hard film to watch, with things going nowhere — in many ways like life in detention.

Boochani said that for people “to understand the film you need to understand chauka as a concept”.

The chauka is a bird native to Manus Island and is explored at length in the film through its place in Manus Island culture, how it sings different songs to signal the time of day and how the Australian government has called the most horrific compound in Manus Island detention centre, where people are sent to be punished, the Chauka compound.

Sarvestani says the chauka’s connection to time was integral to the film’s message. He said: “The most important part of this prison torture is the erasure of time — it drives people to suicide, self-harm.”

Historically, time has always been a part of torture. Australia’s detention system is set up in such a way that time can seem to have no meaning for detainees.

The chauka is also a symbol of Australia’s colonial approach to Manus Island, taking the island’s most sacred bird and using it as the name of the centre’s most inhuman compound.

Chauka, Please Tell Us the Time invites its audience to observe and meditate on what life in detention is like. Its style is the antithesis of many contemporary social impact films. While it may struggle to shock or inspire into action, it gives a poignant view into the detention system.

As an almost anthropological-style film observing life inside Manus Island detention centre, it will certainly take its place in history. Its effect and importance may only become known years down the track.